UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

Project Tiošpáye: on- and off-grid solar for Indigenous community development

1/5/2024

6 min read

Feature

Sarah Townes, CFO and Zero Emissions Network Director of the American Solar Energy Society, introduces a unique project to support innovative housing for the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe in South Dakota.

A single question took NGO the American Solar Energy Society (ASES) down an unexpected but profound path. ‘Does ASES have any Native American mentors, and/or is your team educated about Native communities, so that if Native students wanted to participate in the Mentorship Match programme, they could work with a culturally literate mentor?’

This forthright query came from Red Cloud Renewable (RCR) at the Oglala Lakota Sioux community of Pine Ridge. For 15 years, it has provided renewable energy training to more than 1,000 Native American students in solar heating, off-grid and grid-tied solar systems, tiny homes and reforestation from a campus at Pine Ridge. In the question, RCR referred specifically to ASES' programme that connects energy professionals with those seeking to further their professional development in the energy field.

The answer to the question was no, and it raised important issues given the critical energy and health needs in Native American communities across North America. So we began to educate ourselves. We learned of the forced and failed federal assimilation policies like the Indian Removal Act and the Indian Reorganisation Act which have had lasting impacts, contributing significantly to contemporary challenges such as poverty and violence. These brutal policies disrupted traditional ways of life on every level, leading to systemic inequalities that persist today.

Prior to colonisation, the Lakota were the southernmost of the Great Sioux Nation peoples, seven powerful Teton bands that moved with the migrating buffalo herds, who numbered over 30 million, in what is now the Dakotas, northern Nebraska and southern Wyoming. The buffalo was their sacred animal, and supplied of most of their material needs.

Today, substandard housing, persistent poverty, historic and intergenerational trauma with consequent health outcomes, and lack of consistent and affordable energy all contribute to dire quality of life for the Oglala Lakota Sioux as they do for many Native populations. Pine Ridge has the lowest life expectancy in the US, 15–20 years below the national average. It has a median per-capita income of $900 per month (a sixth of the national average). Arsenic and uranium contamination in local water contributes to cancer rates over five times the US national average. Diabetes is 800% above the national average, alcoholism is 550% greater; infant mortality 300% higher; suicide of teens 150% higher and homicide is 80% above the US average. These statistics paint a picture that the ravages of colonial trauma rage on at Pine Ridge.

Over the ensuing weeks following that pivotal outreach from RCR, as ASES staff studied the history of Pine Ridge and learned about their current challenges, the organisation made a commitment to pursue a grant in hopes that we could provide support to a community lacking sufficient, consistent and affordable energy. We decided to apply for the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem Solving (EJCPS) Grant, an initiative at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in direct response to Executive Order 14096, emphasising the federal government’s commitment to rectifying historical injustices and supporting affected communities like the Oglala Lakota Sioux.

Housing

One current challenge facing Native people at Pine Ridge is poor housing stock, primarily trailers and older houses and cabins, coupled with the high cost of heating and cooling poorly insulated homes in an extreme Dakota climate that can dip down to –28°C in the winter and up to 43°C (and climbing) in the summer. Kerosene, propane and wood, the most commonly used fuels for heat, further degrade indoor air quality in homes which often already face mould issues. These fuels are expensive, and impoverished families sometimes have to make the painful choice between ‘heating or eating’. There are incidents of people freezing to death in their home because of power losses.

These fuels also increase the carbon footprint of the Tribe, and decrease their national sovereignty in having to rely, in the case of kerosene and propane, on the fossil fuel industry. This is especially meaningful as the Lakota people of Standing Rock gained international acclaim in their long-standing fight against Energy Transfer Partners and the Dakota Access Pipeline.

US federal government funds are available through legislation including the Inflation Reduction Act and the newer Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), a $27bn initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and revitalise historically impoverished communities administered through the EPA, as well as sizable initiatives through the Department of Energy and other federal agencies.

In addition to those, a privately-funded housing project implemented by RCR with non-profit In Our Hands plans construction of 22 energy-efficient, 500 ft2, two-story air-crete dome houses. Nine will be homeless shelters, one in each of the nine districts of Pine Ridge; at least 10 will be residences for families living in poverty, and the rest housing for pre-professionals undertaking training at the RCR campus. The domes can be built in less than a week and are somewhat reminiscent in their aesthetic of traditional tee-pee life. They are affordable, scalable, fireproof, tornado-proof, and, with care, repellent of pests and mould. Just one eight-inch space heater operating intermittently on the ground floor warms the building all night, even with snow on the ground outside.

That such structures could efficiently use solar-generated electricity provided the perfect impetus for ASES to support RCR’s efforts, as well as bringing greater solar and workforce training opportunities to Pine Ridge. To bring solar-generated electricity to these dome houses, ASES received a $500,000 EPA grant under the EJCPS programme.

The houses provide a long-requested opportunity for residents to return to homestead living, to the ‘home fire’ of traditional life, out on the open land and away from the dangers, pollution and frustrations of the townships. An intergenerational, compound family unit is the foundation of traditional wellness characterised by the Lakota word ‘tiošpáye’, meaning home and community in the bigger sense, where extended families may remain together for life in cooperative living arrangements out on open land.

However, most land parcels away from the town of Pine Ridge have no mains electricity or water supply, and bringing power to a remote plot costs $16.41/m, typically adding up to a bill of tens of thousands of dollars. The US federal government has funding available for water and septic service for Tribal residents through the Department of Indian Health Services; but it will not consider projects without power.

Solar power

The ASES project aims to overcome this challenge by adding off-grid solar power to at least a few remote new homes, including insulated battery backup energy storage.

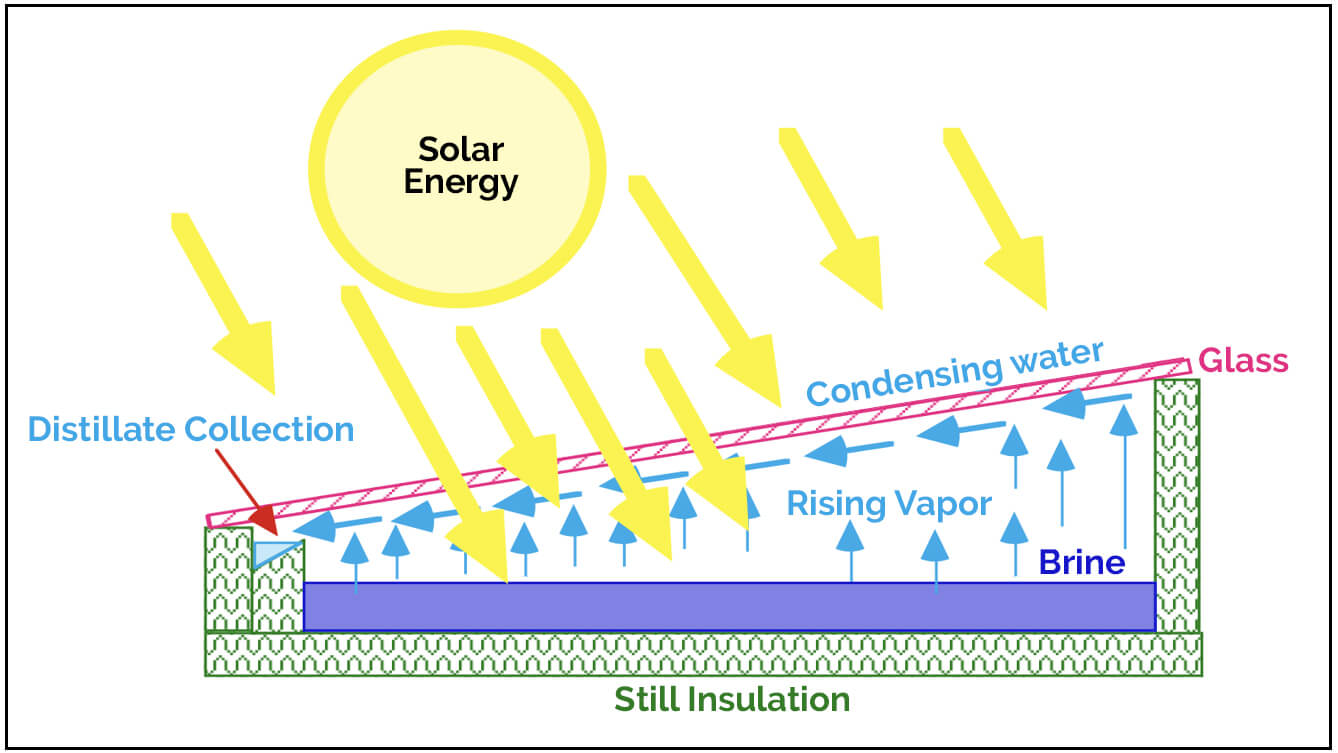

The project also aims to use solar power generation to address other challenges, including clean drinking water. We know that solar distillers can purify water, removing arsenic (see Fig 1). New Mexico’s Sandia National Laboratory is being consulted to determine if they can also remove uranium.

Fig 1: Solar distillers effectively remove groundwater contaminants such as heavy metals, arsenic, bacteria and viruses through evaporation, UV rays, and pasteurisation temperatures

Photo: ASES

Another challenge is fresh and healthy food, as evidenced by high rates of diabetes. As part of the programme, solar water pumps will demonstrate easier water access for gardening, and at least one solar refrigerator to demonstrate affordable food storage.

It is hoped that this project will serve as a pilot to show what’s possible for affordable net-zero living on the reservation, and that future funding opportunities will be drawn in to deploy these models at scale for interested participants. This project will also provide professional experience for Native installers and business owners to prepare them for future opportunities.

Red Cloud Renewable projects

The RCR Solar Training Pre-Apprenticeship Readiness Program trains solar professionals, leading to national (NABCEP) certification. At the most recent programme participants included members of the Cheyenne River, Rosebud, Standing Rock and Pine Ridge Tribal nations. In addition, RCR has also undertaken two other significant projects. The Native-to-Native Energy Sovereignty Project is a path to net zero emissions through energy retrofits, electrification and onsite renewables for Pine Ridge residents. The Bridge programme trains Native women in solar installation and energy entrepreneurship. Both develop a well-trained Native workforce, helping remove cultural barriers in the industry, and use tools and techniques appropriate to local housing stock and remote locations. As part of Project Tiošpáye, students at Red Cloud High School will also participate in training and installations.

Henry Red Cloud has spoken of a prophecy that, seven generations from the height of the genocide, people of all backgrounds would come together to heal and restore the fallen Tree of Life. Chronologically, we are on the cusp of that time. Perhaps more partnerships between organisations like ours and Indigenous peoples can realise the kinds of results this solar installation project and that ancestral vision intend.

Ella Nielsen, Programs Director at the American Solar Energy Society, also contributed to this article.

- Further reading: The Willow project in Alaska faced strong Native American opposition after its approval by US President Joe Biden in 2023.

- ‘How to bring energy to underserved communities’. A fundamental part of the energy transition should involve its justness: ensuring no one is left behind as the world shifts to renewable sources of energy. Find out how expanding energy access and decarbonisation are being aligned in sub-Saharan Africa.