UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

The view from 500 km up

6/3/2024

6 min read

Comment

Jean-Francois Gauthier, Senior Vice President, Strategy, at remote monitoring company GHGSat, reflects on recent changes in national and corporate attitudes to fugitive emissions in the oil and gas sector.

Compared to its predecessor COP27, something remarkable happened last year in Dubai at COP28: we rediscovered our sense of urgency. Countries like Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan joined the Global Methane Pledge. The US, European Union (EU), China and Canada announced sweeping new regulations to address emissions. Fifty international oil companies (IOCs) and national oil companies (NOCs) signed the Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter, a landmark agreement aimed at reducing the industry’s methane emissions and flaring to near zero by 2030.

Cynics were quick to point out that what the world needed was action, not more pledges, but this missed the significance of the moment in several ways.

Firstly, there can be no meaningful climate action without legislative commitment, and pledges are a vital – public – step along that road. A few years ago, for example, some considered Turkmenistan something of a lost cause when it came to emissions. Now the country is part of the international dialogue and forging effective working relationships with the US. In many countries, net zero promises may soon become regulatory requirements.

Secondly, we are seeing an uptick in ‘boots on the ground’ action. Some supermajor operators are now proactively producing detailed emissions reports, explaining the different technologies being deployed and showing progress. The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), meanwhile, is working with NOCs in Iraq, Algeria, Egypt and Kazakhstan, using satellite data to find and fix major methane leaks. In the US, and elsewhere, energy companies now face financial penalties if they fail to report and sort methane leaks in a timely fashion.

Technological progress in monitoring and mitigation are here, and they are mature, ready to be deployed at scale. One of these, satellite monitoring of emissions, provides a third reason for optimism.

GHGSat, which works with industry, governments and scientists, now has 12 high resolution satellites in orbit with plans to measure every emitter in the world every day, in near-real time by 2026 with another four planned satellites. This matters because we can only manage what we can measure. In 2023 we measured more than 361mn tonnes of CO2e in methane emissions from more than 14,000 methane plumes around the world, representing over 80 million cars driving for a full year. Out of this total, less than 10% was confirmed mitigated.

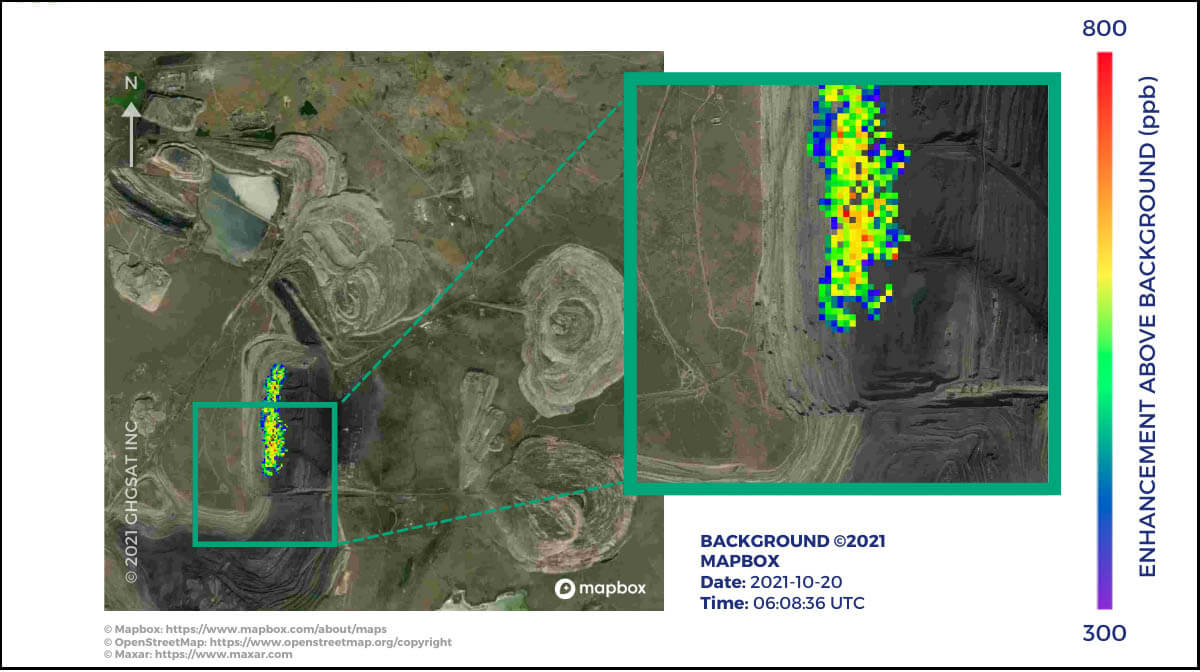

Fig 1: GHGSat methane measurements overlaid on optical-wavelength satellite photograph of coal mine at Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan

Fig 1: GHGSat methane measurements overlaid on optical-wavelength satellite photograph of coal mine at Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan

Source: GHGSat

While removing pollution equivalent to over one million cars is non-trivial, it is also just a small percentage of the global total. But – it shows the opportunity that is right in front of us, ready for the taking.

Not all emissions can be addressed easily. Some are from landfills and coal mines, open pit and underground, where mitigation is more challenging and may require significant capital investment. However, more than half are from oil and gas, where over 40% of mitigations may be achieved at no net cost to the operator. Laurence Tubiana, one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, and Catherine McKenna, Canada’s former Minister of Environment and Chair of the UN’s High-level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-state Entities, recently wrote in Time Magazine that: ‘Tackling methane from oil and gas is one of the cheapest and most effective options to limit warming in the short term.’

The opportunity is right in front of us, ready for the taking.

And yet, just as the prize looks tantalisingly close the world has segued from pandemic into an ever-expanding, multi-polar, geo-political crisis. Will climate momentum be lost again? That is possible. Countries busy fighting – or surviving – may not fret about the difference between 1.5°C or 2°C, unless they can clearly feel the impact of rising temperatures which can themselves become a root cause of increasing conflict. As events currently playing out on the Red Sea remind us, energy security and world-trade are inextricably bound to current events.

However, I believe in our resilience. The satellites will be launched. The artificial intelligence (AI) refined. Leaks will be found. Energy operators will become more efficient, not just because of regulations, or even the moral imperative, but because it makes business sense. An industry that operates wells in 8,000 feet of water is not one easily daunted. It also looks 10, 20 years ahead and if the details on the horizon are vague, at least the direction of travel is clear.

It’s tempting to wait for the next technology, or for inventories to be complete, to start taking action. The reality is that these things must happen in parallel with the action that can no longer wait. We already know where the biggest problems are. Let’s fix them now, then find more along the way. As Tubiana and McKenna noted: ‘Exponentially reducing methane leaks is a problem that countries have the immediate power to solve.’

During a rocket launch, a massive amount energy is required just to get off the pad. Overcoming gravity and inertia produces a prodigious quantity of sound and fury. As fuel burns and the rocket become lighter, it accelerates faster. The upward trajectory is not inevitable but it looks and feels progressively more effortless as the rocket gets higher. Momentum picks up and quicker than you might imagine, the vehicle reaches its destination.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are strictly those of the author only and are not necessarily given or endorsed by or on behalf of the Energy Institute.