UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

End of the ICE Age looms as EV sales accelerate

18/10/2023

6 min read

Feature

Electric vehicle (EV) sales are steadily lapping those of traditional internal combustion engines (ICE) across the globe. But sales are not linear in all markets. And the effect of removal of subsidies cannot be dismissed, along with concerns about having sufficient batteries. Selwyn Parker reports.

Like most revolutions, the one that is making road transport electric was brewing for a long time before it burst on us.

Hardly 20 years ago, EVs were still an oddity on the roads of the western world and almost non-existent elsewhere. Tesla, one of the biggest-selling manufacturers, was only founded in 2003 and its first car, the Roadster, was unveiled in 2008. Although, as automotive historians point out, the first EVs date way back to the mid-1800s and, if Henry Ford had not realised that oil was more abundant than electricity when he designed the Model T, battery-driven cars might have become the standard.

But now the latest numbers continue to confound the pundits. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2023 Net Zero Roadmap, EVs will account for two-thirds of all car sales by 2030 at current growth rates. That forecast is based on the unexpectedly rapid growth of the last five years.

The IEA’s more detailed 2023 Global EV Roadmap, a monumental 140-map survey of the state of the hybrid and all-electric market, describes ‘exponential growth’ in 2022, which saw 10 million EVs sold, 14% of all car sales. For comparison that’s three times the sales in 2020.

Although China, the pioneering EV manufacturer at scale, accounted for an astounding 60% of global sales in 2022, a number that boosts global volumes, EVs are also flying out of showrooms in other regions. Europe saw an increase of 15%, and the US 8%, a highly significant figure in a nation that is historically the world’s biggest gas-guzzler in road transport. Turbo-charged by the Biden Administration’s trillion-dollar attack on emissions, even standout states such as Texas with its anti-EV bias (billing EV drivers an extra $200/y under a new registration fee to make up for lost revenue from gasoline taxes) are starting to snap them up.

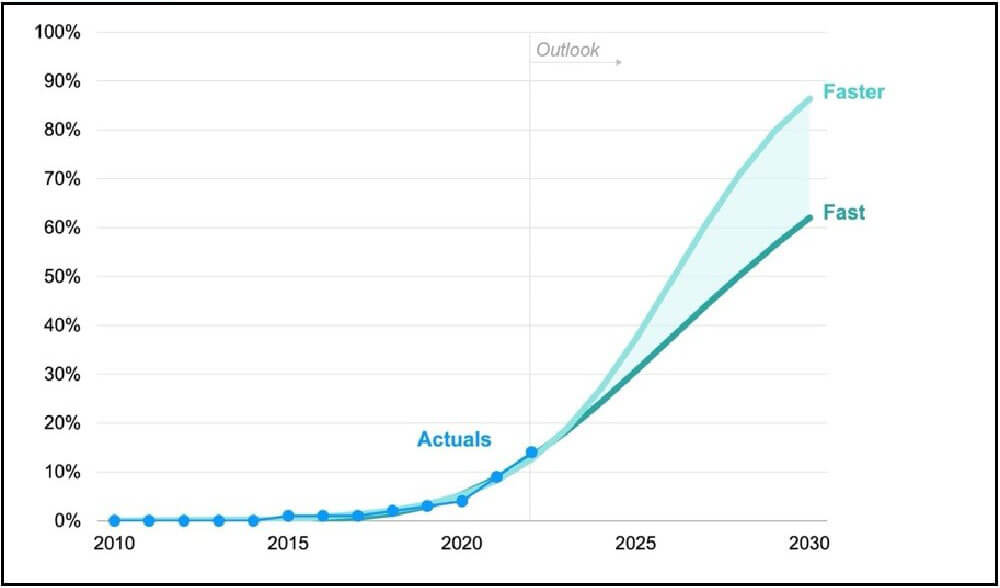

Apart from China, nobody has been forecasting EV volumes on this scale. As America’s respected independent energy consultancy Rocky Mountain Institute points out in a revealing study in September entitled The EV Revolution in Five Charts and Not Too Many Numbers: ‘EV sales are growing exponentially up S-curves and one country after another is taking a similar path.’ Citing long-running numbers, the Institute argues that in broad terms countries tend to jump from an EV market share of 1% to 10% in about six years before the S-curve happens, while thereafter the share hurtles to 80% in the next six years.

Fig 1: Electric vehicles’ share of global car sales – global EV sales have consistently beat forecasts

Source: Rocky Mountain Institute

This appears to be happening right now. According to the IEA, global EV sales in 1Q2023 hit 2.3 million, up by 25% over the comparable quarter in 2022, while other sources see at least similar advances right through 1H2023. Moreover, if oil prices go through the roof again, they are expected to boost sales further.

The increase in sales is not linear. A slow January had analysts questioning the optimism of the IEA and predicting that looming deadlines for the removal of EV subsidies threatened rosy forecasts. Others cited laggard regions such as oil-dependent Africa and much of Asia. As anybody who has been stuck in one of Bangkok’s noisome traffic jams will know, a wholesale conversion to electrically powered transport is a long way off in some countries.

But the penny is dropping even there. EV sales in India, Thailand and Indonesia more than tripled in 2022 over the previous year, albeit up to just 80,000 units from a low base. Yet increases respectively of 1.5% of total sales in India and Indonesia, and 3% in Thailand, all of them on the back of sales-boosting government action, are not insignificant because they reflect what has already happened in the western world.

That’s just cars. It is often forgotten that, although western buyers prefer bigger cars, the world’s biggest fleet of electrified vehicles is composed of little two and three-wheelers found in emerging and developing countries.

In India 90% of its three million EVs are two and three-wheelers, although until recently the vast majority were petrol-fuelled. But in 2022 over half of all the registrations of these ‘auto-rickshaws’ were electric as the lower through-life costs are better understood in a highly traditional market. For instance, a start-up in Delhi called Zyngo EV Mobility runs an all-electric fleet of three-wheelers to make about 20,000 deliveries a day because they are cheaper.

Amazon is piloting three-wheel electric delivery vehicles across India

Photo: Amazon India

Then there are (four-wheeled) trucks and buses. Globally the sales of what are known as ELCVs (electric light commercial vehicles) soared by over 90% in 2022. Although it won’t happen overnight, the heavy-duty vehicle (HV) market is also changing its spots. According to the IEA, a total of 220 new models of electric HVs entered the market in 2022, bringing the total market to 800 different models.

End of subsidies

The effect of the progressive removal of subsidies cannot, however, be dismissed. Abhishek Murali, Clean Tech Analyst at consultancy Rystad Energy, writes: ‘The sands are shifting for the global EV market. Consumer appetite for electric cars remains strong, but it’s clear that tax credits and subsidies still play a significant role in convincing consumers to make the switch. Carmakers may have no option but to respond with reduced prices.’

Although the level of subsidies just about everywhere except the US is falling, the launch of cheaper and smaller models, such as the low-budget Oro from China’s Great Wall Motors, is expected to compensate. At last count, there were 500 EV models of all sizes, twice as many as five years ago, and increasingly they cover the market spectrum.

Also, manufacturers are steadily achieving economies of scale in an increasingly competitive market. As prices fall consumers are expected to buy as much on price as on ecological virtue.

Furthermore, prices are coming down. Trade publication Car Guru notes high double-figure falls in the average listing prices in the US for the following used EVs between July 2022 to July 2023: Tesla Model S down 42.1% from $73,751 to $42,669, Kia EV6 down 32.7% from $63,939 to $43,035, and the Ford Mustang Mach-E down 32.1% from $65,176 to $44,250. A healthy second-hand market is also seen as underpinning new sales.

However, prices are not falling fast enough for some. Responding to statistics that show EVs to be moving slowly out of some American showrooms, activist Deanna Noel of the Public Citizen’s climate programme laid the blame on the automotive giants: ‘Auto companies like General Motors should be hastening and prioritising production of affordable, smaller EV models to meet booming EV demand – not slowing.’

Doubts about batteries

Will there be enough batteries to meet the revolution? Currently, there aren’t. Some manufacturers, including GM, are running short mainly because of high demand for lithium-ion, the mineral of choice. But new battery manufacturing techniques are emerging and, reluctant to rely on China’s domination of the industry, the European Union, UK and US are boosting domestic production.

Meantime though, the downside to growing sales of EVs is the carbon-heavy production of the batteries. Hence a lot of money, science and energy is being poured into how batteries are produced as well as into how many.

Although the emissions of EVs over their lifetime once they get on the road are much lower than those of gas-powered vehicles, they are more polluting to produce. The Rocky Mountain Institute estimates an EV puts out roughly twice as much carbon during the manufacturing process as do fossil-fuelled vehicles. ‘And of that carbon footprint, 40–60% of emissions come from production of the large lithium-ion batteries used to power EVs,’ the consultancy concludes.

A big part of the problem is the enormous distance – an average of 50,000 miles (80,500 km) – that the essential minerals have to travel to get to the battery manufacturer.

In the issue of carbon emissions not all battery manufacturers are equal. The dominant manufacturing nation, China, with 70% of the market, also has the most emissions-intensive production processes. An analysis by McKinsey finds that China’s emissions exceed those of rival manufacturers in the US by up to 45%.

In theory at least, the circular economy offers a solution and President Biden’s Administration is pouring money into creating one. More than $7bn has been put aside to help bring the production process onshore while last year the US Department of Energy, which is in the middle of the Inflation Reduction Act, handed $2.8bn to 20 companies to help make it happen. The government money is just the tip of the iceberg – a wide range of manufacturers sitting along the supply chain have since 2020 committed no less than $75bn to domestic production of EV batteries and, critically, to recycling them into a second life such as energy storage before they reach the end of their lives.

Overall though, the EV revolution is good for the planet. Nevertheless, Westerners prefer big cars, as the long-running boom in ICE-powered SUVs (sport utility vehicles) shows. Unfortunately, they emit more than their fair share of pollutants – in 2022 fossil-fuelled SUVs pumped out over a gigatonne of CO2. But on the bright side, the IEA calculates that the current fleet of electric SUVs is slashing the consumption of fossil fuels by over 150,000 b/d of oil.