UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

Reinventing heavy industries

7/6/2023

6 min read

Feature

Energy Institute Knowledge Manager Kinga Niemczyk looks at how energy intensive industries and their workforces will play a central role in the decarbonisation of economies around the world.

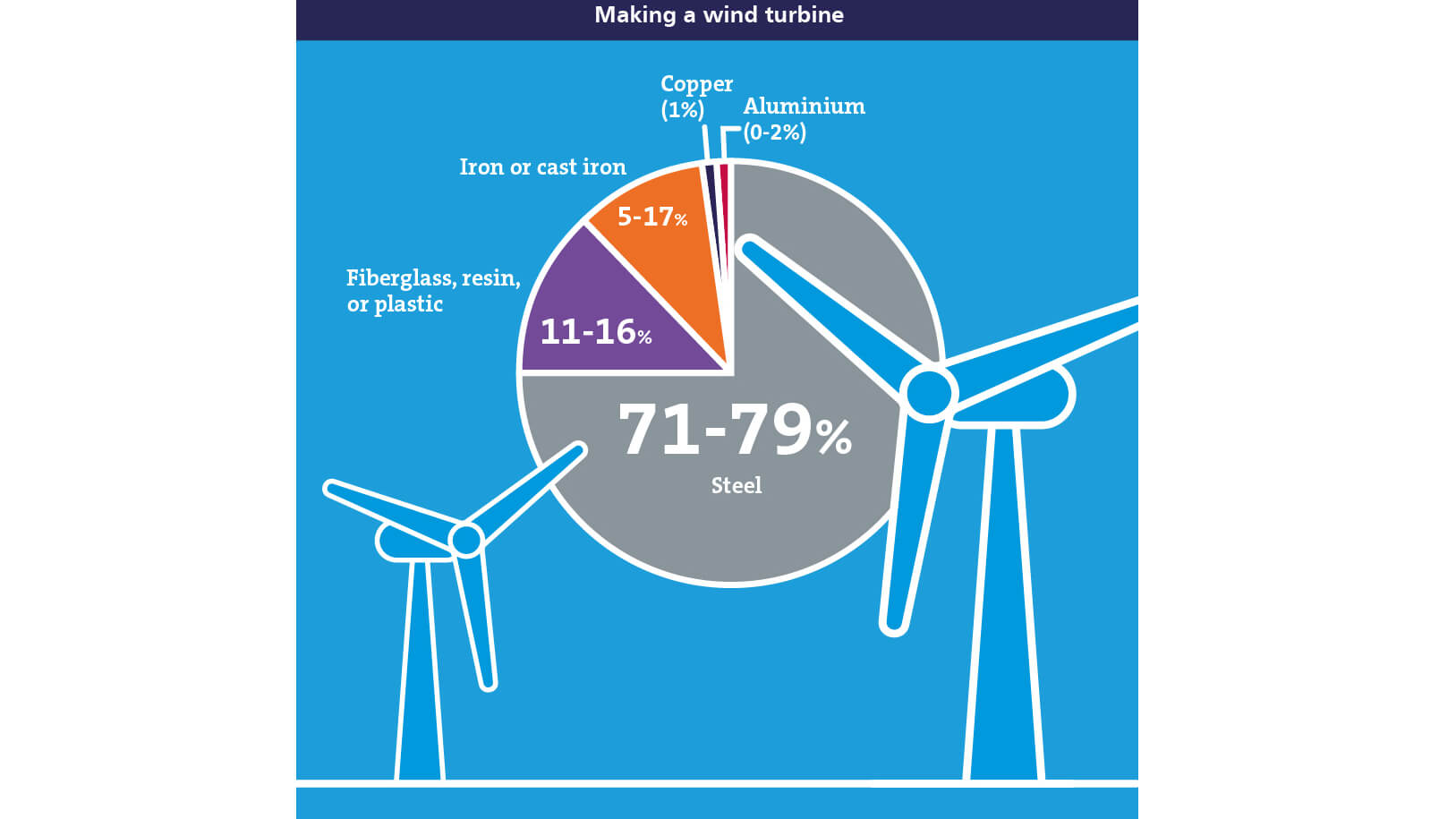

Images of dense smoke coming from enormous factory chimneys, sparks flying from overheated furnaces, and large carbon footprints often come to mind when we think of energy intensive industries, such as those involving steel, iron, aluminium and chemicals. It is rare to associate these sectors with the production of wind turbines, solar panels, heat pumps, semiconductors, batteries and electric cars.

But paradoxically, both visions are true – energy intensive industries are contributing significantly to the climate change crisis, while at the same time being essential for producing outputs necessary for the net zero future.

Energy intensive industries are crucial for the energy transition, not only because of the importance of their products to the renewables sectors or for the electrification of heat and transport. Due to their central position in economies, their interconnection with the energy system, their reliance on fossil fuels and very high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, delivering net zero targets won’t be achieved at the necessary speed and scale without decarbonised industries.

Decarbonisation of these hard-to-abate sectors is yet to gain the momentum already seen during the transformation of the electricity sector over the last decade. The task at hand is more difficult as the use of fossil fuels is more deeply embedded in the production process.

Various materials are needed for constructing vital renewables infrastructure such as wind turbines

Source: Energy Institute

Movement in the right direction

However, the industrial decarbonisation trend has undoubtedly been developing over the past couple of years, even if it’s predominantly at the research and development level. This is partially dictated by climate change concerns, government policies (eg the UK’s Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy 2021), but also by simple survival calculations in the era of the recent energy crisis, largely caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which exposed energy-intensive industries to volatile changes in energy prices.

Most analysis and discussion about how to transform industrial processes focuses on fuel switching to low-carbon hydrogen or electricity, the deployment of carbon abatement measures such as carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS), or the development of other future low-carbon technologies, well suited to idiosyncrasies of various industrial sectors.

The majority of the UK government’s efforts and funds are also focused on technologies and innovations. For example, the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund, which provides funding for developing and deploying technologies that enable businesses with high energy consumption to transition to low carbon; the Industrial Decarbonisation Research and Innovation Centre (IDRIC), which aims to create the world’s first net zero carbon industrial cluster through large-scale decarbonisation solutions; and through the funding of industrial clusters to develop shared infrastructure.

People and skills

However, carrying out a broad, complex and expensive transformation in energy intensive industries will not be possible without a skilled and knowledgeable workforce. This challenge could even eclipse technology as the biggest barrier to meeting net zero, according to the Energy Institute’s 2021 Energy Barometer report.

But it is not being given due attention. Upskilling and retraining the current workforce as well as attracting new talent is all the more fundamental at a time of automation and increasing sophistication of artificial intelligence (AI). Often described as the ‘fourth industrial revolution’, the changes that industries are currently undergoing are more than just technological development. They are having a transformative effect on the economy, politics and society at large.

Currently, industrial companies are estimated to provide about one-quarter of global employment, as they also support many jobs indirectly throughout the supply chain. In the UK alone, industrial sectors provide around 2.6 million direct jobs.

The energy transition and digital transformation have eliminated millions of jobs in energy intensive industries worldwide, but also opened doors to a variety of new jobs, as reported by Randstad. These new jobs require new skill sets, such as data analysis, digital skills (including digital security), climate skills (eg awareness of climate transition challenges, climate finance, geographic information system [GIS] mapping).

Importantly, the required skills will rapidly evolve as technologies mature or new solutions are invented. Hence, industries will look for workers whose skills and knowledge are keeping pace with changes, who are creative with critical thinking and problem-solving attitude, and with many other competencies besides.

It’s also true that many existing skills in energy intensive industries, such as precision working, equipment management, engineering, construction and project infrastructure skills or energy system knowledge are transitionary and can be used in a different context or process than in the net zero economy. Undertaking training to reskill in certain areas allows for manoeuvrability between different industries and helps to future-proof careers by creating long-term job security.

For example, a technician may need a hydrogen safety course to learn about the safety aspects of fuel switching between natural gas and hydrogen but does not necessarily need an overhaul of their job.

The future looks bright

Europe has over 1,500 industrial clusters, representing 54 million jobs or almost 25% of total employment in the European Union. A shift to a resilient, net zero economy will generate up to 37 million additional jobs worldwide by 2030.

There were already over 410,000 jobs, specifically in low-carbon businesses and their supply chains, in the UK in 2021. The UK government is investing £4bn into this growing sector to support two million green jobs in the UK by 2030.

Decarbonisation will play out differently in each sector, shaped by when individual technologies reach commercial maturity. This means that a wide variety of job opportunities are becoming available. The industrial sector has been described as an ‘employees’ market’, where industries will compete for these skills sets.

In the UK, skills and competencies such as construction and project infrastructure skills will be in high demand, with major infrastructure projects such as CCUS and hydrogen plants, High Speed Two (HS2) and Hinkley Point C nuclear power station competing for the same people. Many businesses are predicting shortfalls in the availability of suitably qualified and experienced personnel to fill critical roles – with some businesses are already experiencing this.

Moreover, these sectors will need to improve their diversity, particularly at senior levels. According to a Deloitte report in 2021, fewer than one in three manufacturing professionals in the US were women. The latest annual board statistics published by POWERful Women (PfW) show that only 16% of executive director roles in the UK energy sector are held by women and there are just six female CEOs in the top 80 UK energy companies.

Creating the workforce of tomorrow, today

Building the skilled industrial workforce of the net zero future requires a concentrated effort by workers, companies, educational institutions and the government. It is common for people to have to fund training themselves and take time off to complete their studies. Nearly half of respondents to the EI Energy Barometer 2021 had concerns about cost, time and availability of courses standing in the way of their skills development. This is a significant barrier, particularly without certainty of demand.

These concerns could partially be addressed by companies offering in-office training, by supporting enrolments to free online courses, or by encouraging attendance at live or online workshops. Most of all, the government should lead the way – first by providing long-term, stable energy policy that creates commercial drivers for the skills of tomorrow, and second by developing a national net zero skills strategy to identify these skills and focus on their development, from school onwards.

While reaching net zero is the fundamental goal, decarbonisation of energy intensive industries may provide much more than technological advancement and emissions reduction. It is an opportunity to equip workers in the industry with better tools, give them better information and enhance their capabilities. Ultimately, it may transform the UK’s industrial regions and cement the country’s position as a global leader in building the workforce of the net zero future.

The Energy Institute’s Energy Essentials: Transitioning energy-intensive industries to net zero guide provides further information for understanding some of the challenges and opportunities of working in, living near, buying from and supplying energy-intensive industries as they move towards net zero GHG emissions.