UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

Shipping looks to the past for a cleaner future

9/11/2022

6 min read

Feature

Wind power as a renewable alternative to fossil fuels is not limited to offshore and onshore turbines. Nearly 250 years after the world’s first steamship, the global shipping industry is once again seeking to harness the power of the wind, reports Selwyn Parker.

Almost overnight, the ocean’s biggest ships have started tapping the long-neglected virtues of sail power in a quest to slash costs and emissions. In a flurry of activity during the last year or so, operators of the behemoths of the sea such as bulk carriers, car carriers and tankers have started harnessing the wind or are conducting trials.

Depending on the size of the vessel – and some tip the scales at over 300,000 deadweight tonnes (dwt), the expected savings range from anything between 4% and 50% in fuel consumption and emissions.

As things stand, it is highly likely that 2023 will go down as a formative year for giant wind-powered vessels as they follow in the wake of coastal traders, ferries and other smaller ships that have been using sails for the last three or four years.

Sailing ahead

According to the International Windship Association, no less than 21 large ocean-going vessels with a combined cargo capacity of 1mn dwt boast wind-propulsion systems. By the end of 2022, the trade body expects another four big ships to follow suit.

Right on cue, one of the world’s biggest charterers of vessels, commodities group Cargill, is conducting trials that could accelerate wind power. It has installed two hard sails on a dry bulker and will evaluate the results over three to six months. The President of the group’s Ocean Transportation Division, Jan Dieleman, is optimistic, estimating that emissions could be slashed by 30%, with roughly commensurate savings in fuel.

The group chartered between 600 and 700 ships, transporting some 240mn tonnes in the last financial year, and a shift to wind-assisted vessels would send an important message.

Several other bulk-carriers are following suit. Japan’s Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL) will put its Wind Challenger hard sail and a rotor sail on a ship destined to carry wood chips for a US company. A pioneer in wind-powered big ships, MOL has been developing the system over 14 years.

Not to be outdone, in late September China’s Dalian shipyard launched one of the biggest wind-assisted vessels ever. It’s a very large crude carrier (VLCC) called New Aden. A class that can carry 2.5mn tonnes of cargo, the vessel will be partly propelled by four rigid wing sails. Weighing in at 307,000 dwt, the New Aden will cut average fuel consumption by nearly 10% on its regular route between the Middle East and Far East, according to the China Classification Society that oversaw the installations.

A long-awaited sail-powered project is Japan’s Peace Boat cruise liner, the Ecoship. Originally due to be launched in 2020, construction has been delayed by COVID-19, but it promises to set new standards for big wind-assisted ships. At 225 metres long and 31 metres wide, the 2,000-passenger vessel will be propelled by LNG-fuelled engines that can be switched to biofuels when they become available, 10 retractable sails and 10 wind turbines that are also retractable, and 12,000 m2 of solar panels.

Peace Boat’s Ecoship cruise liner will harness energy from the wind, the sun and biofuels

Peace Boat’s Ecoship cruise liner will harness energy from the wind, the sun and biofuels

Photo: Peace Boat

And at the other end of the scale, UK-based Smart Green Shipping believes its FastRig wing sail technology can deliver ‘at least 20% fuel savings and as much as 50% for small and medium-sized newly built ships’, according to founder Diane Gilpin. A FastRig will be trialled on the sea in 2023, with ease of operation a priority. In fact, the crew only need to press buttons to make it work.

The wind is free

The wind is free. Yet shipping has largely ignored it since sail-powered cargo vessels all but disappeared from the world’s oceans early in the last century. Now the penny is dropping. As Gavin Allwright, Secretary of the International Windship Association, says: ‘The industry is waking up to the fact that wind-assisted – and primary wind – propulsion systems are needed in the toolbox of decarbonisation solutions. Perception has shifted, especially in Europe but increasingly in Asia too.’

Quite suddenly, shipowners are spoilt for choice. Depending on the size of the vessel, the route and the prevailing winds among other factors, they can decide between rotor sails, hard or rigid sails, soft sails, kites, suction wings, turbines and even an inflatable wing sail being developed by Michelin under its zero emission Wisamo project. Currently, the tyre manufacturer’s sails are being trialled on a 12 metre long yacht, but the plan is to scale them up as time goes on. Most of these sails can be retracted or lowered to pass under bridges if necessary.

Making wind power shipshape again

Some of the wind-harnessing technology harks back hundreds of years – and China may be ahead of the game. Near Shanghai, the Jiangang Shipyard derives its Smart Sail from the junks – or sand boats – that have plied coastal waters for centuries. Made of polymer composite materials rather than the linen or matting of earlier times, the rectangular Smart Sail can cut fuel use by up to 4%, according to Jiangang.

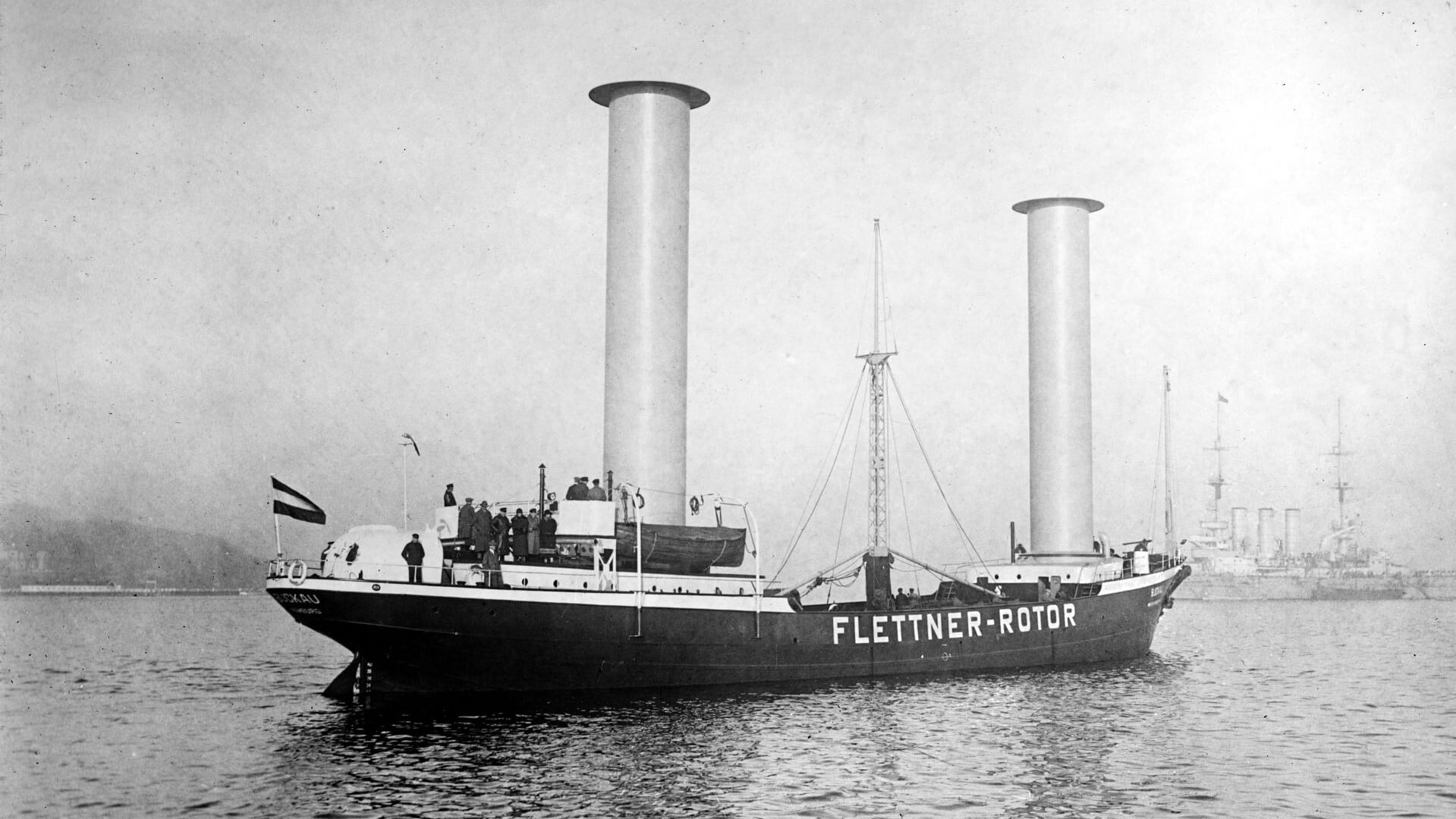

South Korea’s largest shipyard, Hyundai Heavy Industries, hopes for even better, up to 8%, with its Hi-Rotor sail. This technology is over a century old, having been developed by Anton Flettner, a German aviation engineer who calculated that a spinning cylinder could capture wind and speed it up in what is known as the Magnus effect. A rotor-powered ship crossed the Atlantic as long ago as 1925, but at that time the shipping industry was turning its back on sails.

Setting things to right, a 2021 study of a rotor-equipped bulk carrier operating between the port of Damietta in Egypt and Dunkirk revealed how far Flettner was ahead of his time. ‘Economically, the results reveal that the use of Flettner rotors will contribute to considerable savings, up to 22.8% of the annual ship’s fuel consumption,’ the study concluded. Payback would come within six years while nitrogen and sulphur emissions would be substantially reduced.

The original Flettner rotor vessel from the 1920s

Photo: Flettner

According to operators, it is too early to say which technology will prevail but in the meantime there’s a trend towards two or more types of sails because of the versatility they offer. In the Netherlands, the Optiwise Horizon project, which is studying the use of multiple systems, is confident of the benefits, estimating energy savings could be as high as 30–50%.

One of the partners in the project is tanker giant Euronav, whose sustainability manager Konstantinos Papoutsis explains, citing the shortage and high price of zero emission fuels: ‘Energy saving onboard is expected to be increasingly important, both environmentally and economically.’

The clock is ticking

The deadline for the International Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) tough new standards for energy efficiency (EEXI) and carbon emissions (CII) come into effect next year. The global shipping fleet accounts for about 3% of the world’s CO2 emissions. Although that’s low compared with the pollution caused by land-based transportation, about 90% of the world’s trade goes by sea. And during the COVID-19-triggered demand for sea-borne cargoes, many ships had to abandon lower-emitting slow-steaming strategies and increase speeds, burning more fuel.

Despite considerable efforts by the industry in the form of cleaner-burning engines, more efficient propellers and less resistant hull designs among many other innovations, emissions aren’t coming down fast enough for the IMO.

The way forward in wind power has been shown by smaller vessels, like the ferries of the Danish-German group Scandlines. Following successful trials on a sister ship sailing across the Baltic Sea to Denmark where prevailing winds are favourable, in mid-2022 the group installed a second non-retractable rotor sail on its hybrid-powered Berlin. According to Chief Operating Officer Michael Guldmann Petersen, the chimney-like sail achieved targeted reductions in CO2 emissions of 4–5%.

There have been teething troubles. For instance, some sails, both hard and soft, have had to go back to the workshop after being battered by storms while some crews had a steep learning curve in how to get the most out of them.

Back to the future

But the general conclusion is that wind power is here to stay, and emissions-conscious governments are pouring money into them. Mitsui’s Wind Challenger programme is funded from Tokyo while Scandlines’ rotor sail is one of the beneficiaries of the Wind Assisted Ship Propulsion (WASP) project supported by a €4.5mn grant from the European Regional Development Fund.

Brussels has high hopes for wind-powered ships. A European Union report estimated up to 10,700 installations by 2030 while the UK’s Clean Maritime plan is even more ambitious, anticipating about 40,000 vessels – or up to 45% of the fleet – will be sail-driven to some extent by 2050.

While it’s unlikely that big ships will be entirely powered by the wind, some smaller cargo vessels already rely 100% on it. Brittany’s Grain de Sail has done so well with a schooner that it has placed a €10mn order for a bigger, all-aluminium version that, rather like the clipper ships of old, will transport fine products such as coffee, chocolates and wines across the Atlantic, using a small motor only for docking. The yacht will have a payload capacity of 350 tonnes and each crossing should take two weeks with a crew of about nine. And of course, the voyage is as zero emission as it’s possible to be.