UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

How the circular economy could make electric heat affordable

6/4/2022

6 min read

Feature

Decarbonisation of domestic heating in the UK implies a shift from gas to electricity in many cases, but electricity can cost three times as much. Here, Dr Garry Felgate FEI, Chair of Thermify Holdings, discusses the options and introduces a novel ‘circular economy’ option.

The climate crisis (and the cost of living) is high on the UK agenda, with the UK government planning to deliver net carbon zero by 2050. The domestic householder will see the transition via the electrification of transport and the electrification of heat.

Looking at the alternatives, according to EDF Energy the cost of an electric vehicle (EV) charging at a public fast charging point is about £6–7 for 30 minutes, giving a range of about 160 km. A modern, highly fuel-efficient VW Golf will deliver a fuel consumption of 4.5 litres/100 km (equivalent to 52 mpg). At today’s pump price of £1.80/l, 160 km will cost just under £16. Like for like, electric cars cost under half the price of petrol. The price is lower still if the driver can charge from home.

However, the same is not the case for heating and hot water. Most homes in the UK are heated by gas. There have been significant changes in energy prices recently, particularly those of gas. Using Ofgem’s current caps for standard tariffs in the north-west of England, gas costs 8.3 pence/kWh and electricity is 24.7 p/kWh. Electricity is three time the price of gas. This ratio has come down recently, but still makes electricity considerably more expensive than gas.

All too often, policy makers look at supply side solutions for green energy – however, the cheapest unit of energy is the one that you don’t use.

The greening of our heating has the potential to significantly increase the 13% of households in England and 25% in Scotland who are defined as fuel poor – proportions which are bound to increase with rising gas prices. Research by National Energy Action suggests that 6.5mn homes could be in fuel poverty right now.

This reduction in gas use is also a key driver for other countries. I have recently returned from living in Germany, where gas is also the main source of heat. During the recent Federal elections there was widespread discussion over the opening of Nord Stream 2 to provide gas from Russia. Following the election of a new government – with the Greens becoming a key coalition party – and the tragic events in Ukraine, Germany has put on hold the opening of the pipeline and is reconsidering its heating approach away from gas.

Given there will be a move to greater electrification of heat, how do we do this without causing real hardship for many people? How do we deliver clean, affordable heat?

We do it with a circular economy approach:

- reduce domestic energy demand;

- shift demand to lower cost times;

- make electricity use much more efficient; and

- as in Thermify’s solution (see below), have someone else pay for a part, or all, of the electricity costs.

Demand reduction

We have had feed-in tariffs (FiTs) to drive the use of local generation, so why not FiTs for energy reduction?

All too often, policy makers look at supply side solutions for green energy. However, the cheapest unit of energy is the one that you don't use. The most effective way of delivering affordable heat, whatever its source, is always to reduce demand whilst at the same time increasing comfort.

Using the very useful lenders tool from epcmortgage.org.uk, at the time of writing a three-bedroomed house in the UK will have fuel bill of £475–644/y for an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) A; £1,080–1,435 for an EPC C; and up to £1,765–2,389 for an EPC G. Using this tool shows an annual reduction in fuel bills of between £170–250/y just by going from EPC D to C for a three-bedroomed house.

We have had incentives for green generation, FiTs for solar, the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). Why not a FiT for energy that the householder does not use, delivering faster payback for energy efficiency measures?

The reduction of VAT on many energy efficiency measures is welcome. A highly energy efficient new home need not cost more than an average one.

Shift demand

Time of use (ToU) tariffs should be further widened so that more electricity can be used at times of plentiful generation. Night-time tariffs are familiar and can be very effective.

We would take this to a more granular level. Brazil has introduced a ‘white tariff’ with a view to reducing stress on the network. From 21:30 to 16:30 electricity is 68% of the standard/intermediate tariff, from 16:30 to 17:30 and 20:30 to 21:30 electricity is at the intermediate tariff (100%), and from 17:30 to 20:30 it is at a peak tariff of 152% of the standard/intermediate tariff.

On this tariff, it is estimated that users could reduce their overall electricity costs by around 15% with careful use of electricity. Making greater ToU differences can reduce further the costs of electricity.

Smart homes can take minute-by-minute price signals and smart appliances can operate when these signals are clear, such as cooling the freezer or heating the hot water tank a little.

EVs can also help shift this demand. As a battery, the EV can supply power to the home at times of high demand and potentially higher prices. The EV can then be charged overnight at times of low demand. Suppliers in the UK, such as Octopus, are already offering low charging prices between 00:30 and 04:30.

Efficient use of electricity

Most heaters, electric or otherwise, waste energy. Heat pumps, by contrast, produce more heat than the electricity they consume. The amount of extra heat is expressed as the Coefficient of Performance (COP). The COP can be as high as four, meaning that a well-functioning heat pump can go a long way to overcoming the difference in the price of electricity to gas.

According to GreenMatch, the COP for air source heat pumps drops in colder weather. The COP is about 2.5 when the outside air temperature is 0°C, so while there will be significant savings when compared to other heating methods, the householder will still face high bills in the very cold months. Ground source heat pumps can deliver more even COPs over the year and further reduce the differential costs of electric heating, although they cannot be used as widely and have higher capital costs.

Heat pumps are an effective means for heating homes, particularly when combined with insulation as described in demand reduction. Heat pumps can also form part of district heating systems. For example, heat pumps are currently providing 8% of Helsinki’s district heating demand. These heat pumps are using, in part, waste hot water from commercial sources.

Someone else pays the bill

Many processes, such as manufacturing, IT and others produce significant and increasing quantities of waste energy. In many cases the main product is heat. The tungsten light bulb was, in effect, a heat source rated in power (Watts) not light (Lumens) that produced light as a by-product.

One of the biggest producers of heat is computer processing. Heat is made as zeros and ones flow through the system of scores of datacentres. As much as 30% of the cost of running a datacentre is in cooling the machines. Can this waste heat, which is already paid for, be put to better use?

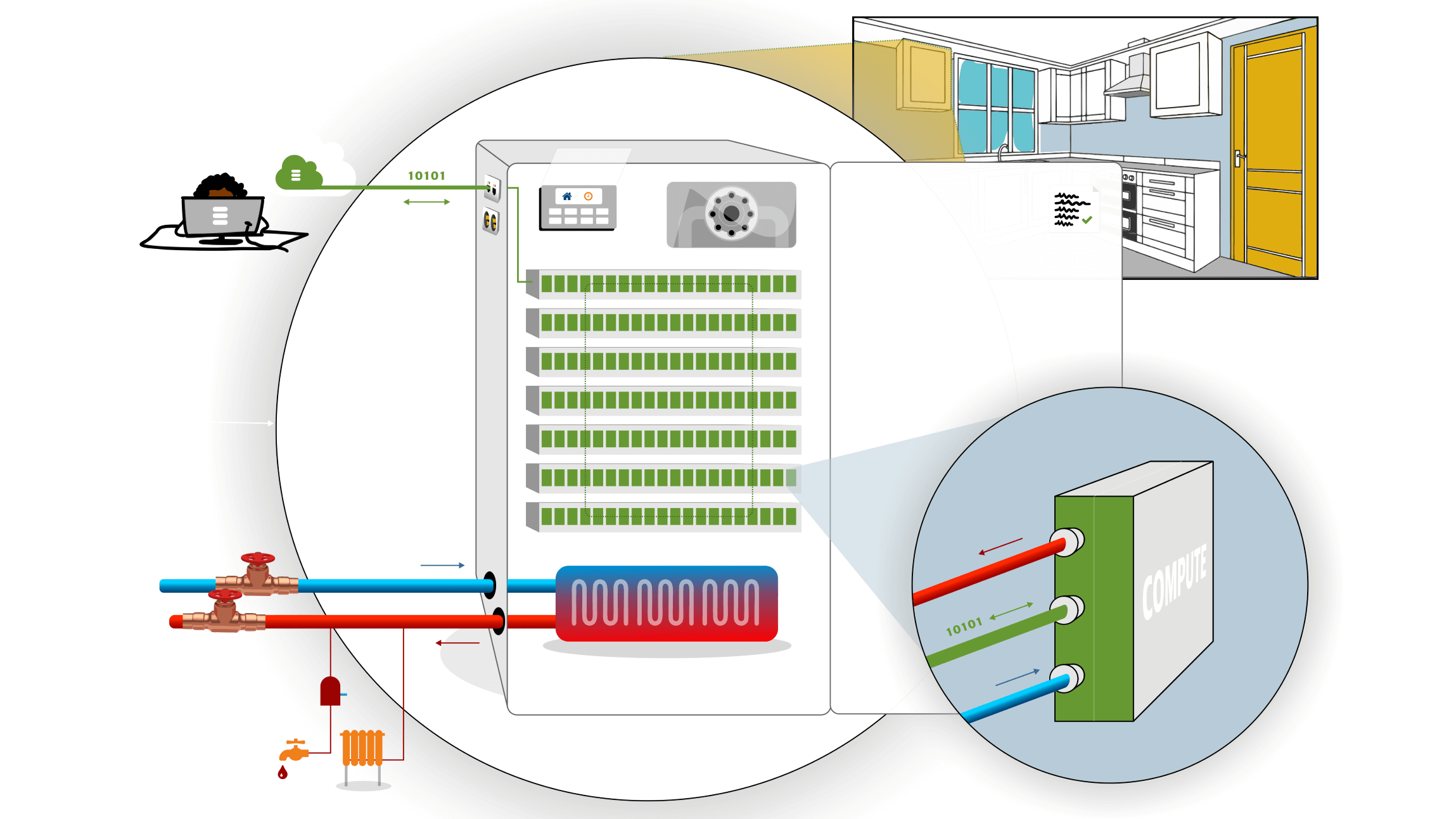

My own company, Thermify, has developed a ‘HeatHub’ that provides heat and hot water in the home. Instead of a gas connection, there is a data connection for it to receive computing jobs from a decentralised queue. Inside the cabinet, which is a similar size to a gas boiler, are hundreds of microprocessors doing those jobs, paid for by the many companies who want to undertake cloud computing. All the electricity is paid for by Thermify, not the householder, yet the householder will receive all the heat – enough to keep the house warm and heat the hot water.

In effect it uses energy twice, a circular solution to providing heat paid for by the company doing the processing. The householder will still pay for the electricity for their home use, dishwasher, lighting etc and for the home broadband use, but all the electricity and data connection for the HeatHub will be paid for by Thermify.

The householder will see a unit similar in size to a gas boiler and will also have a hot water tank. There will be no need for a gas connection. The system will work on standard fibre to the street-box system, as widely provided by Open Reach. Faster broadband services such Fibre-to-the-Home will facilitate faster computing turnaround times.

Analysis by the Energy Systems Catapult shows that the HeatHub is more than capable of providing adequate heat to a home built to current building standards and, with some non-intrusive improvements, can supply the heat and hot water to a typical semi-detached home. The HeatHub will require longer pre-warm times at start-up when compared to a gas boiler – but this likely to be similar to heat pumps.

The analysis says: ‘The Catapult’s Energy Launchpad team has been tracking Thermify for a while and were delighted to be able support them at a critical stage of the product development with funding from Innovate UK. Using the Catapult’s Home Energy Dynamics modelling software we were able to validate the performance of their innovative solution in typical UK housing stock and the associated heating and hot water demands.’

Thermify proposes to provide this heat and hot water to the householder for £50/month, significantly lower than today’s cost of heating a home by gas which in turn is lower than the electric solution.

It is time that we look at how we can use electric heat from other sources that are already paid for by someone else’s work – a circular economy solution that can electrify our heat without massive costs to the householder.

Fig 1: How a HeatHub ‘boiler’ might work

Source: Thermify