UPDATED 1 Sept: The EI library in London is temporarily closed to the public, as a precautionary measure in light of the ongoing COVID-19 situation. The Knowledge Service will still be answering email queries via email , or via live chats during working hours (09:15-17:00 GMT). Our e-library is always open for members here: eLibrary , for full-text access to over 200 e-books and millions of articles. Thank you for your patience.

New Energy World™

New Energy World™ embraces the whole energy industry as it connects and converges to address the decarbonisation challenge. It covers progress being made across the industry, from the dynamics under way to reduce emissions in oil and gas, through improvements to the efficiency of energy conversion and use, to cutting-edge initiatives in renewable and low-carbon technologies.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) has been around for a decade or more in the UK, as a concept, but project development was initially very slow indeed. However, the recent evolution of multi-organisation, yet local, capture and use projects may well change the industrial landscape. Nick Cottam has been asking questions.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report is a stark reminder that what we do to the planet matters. Where we build, how we travel, how we manufacture and, at the most extreme end of the spectrum, when and where nations choose to wage war, can all have a profound impact on the global climate. Whatever is happening in the world, the IPCC notes: ‘The rise in weather and climate extremes has led to some irreversible impacts as natural and human systems are pulled beyond their ability to adapt.’

So, no punches pulled there then, and a sobering sequel to all the transition discussion at International Energy Week 2022. Just like politicians trying to deal with the posturing of President Putin, the world has to adapt to head off climate change and energy remains at the heart of this challenge.

The message around International Energy Week and the energy sector at large is for a realistic transition which finds new ways to fund innovation and remove carbon from all types of energy, from existing fossil to the rainbow bandwagon around different shades of hydrogen. As David Phillips of Aker Carbon Capture Norway noted: ‘We need more working examples of how to decarbonise…’ and carbon capture, you could argue is a case in point.

There is some evidence that the process of capturing carbon, or carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) as it’s now known, is at last coming of age. Expensive end-to-end projects relying on a single operator and without sufficient government incentives are being replaced by more collaborative initiatives whereby costs can be shared, and decarbonised energy can more directly be made available to industrial processes.

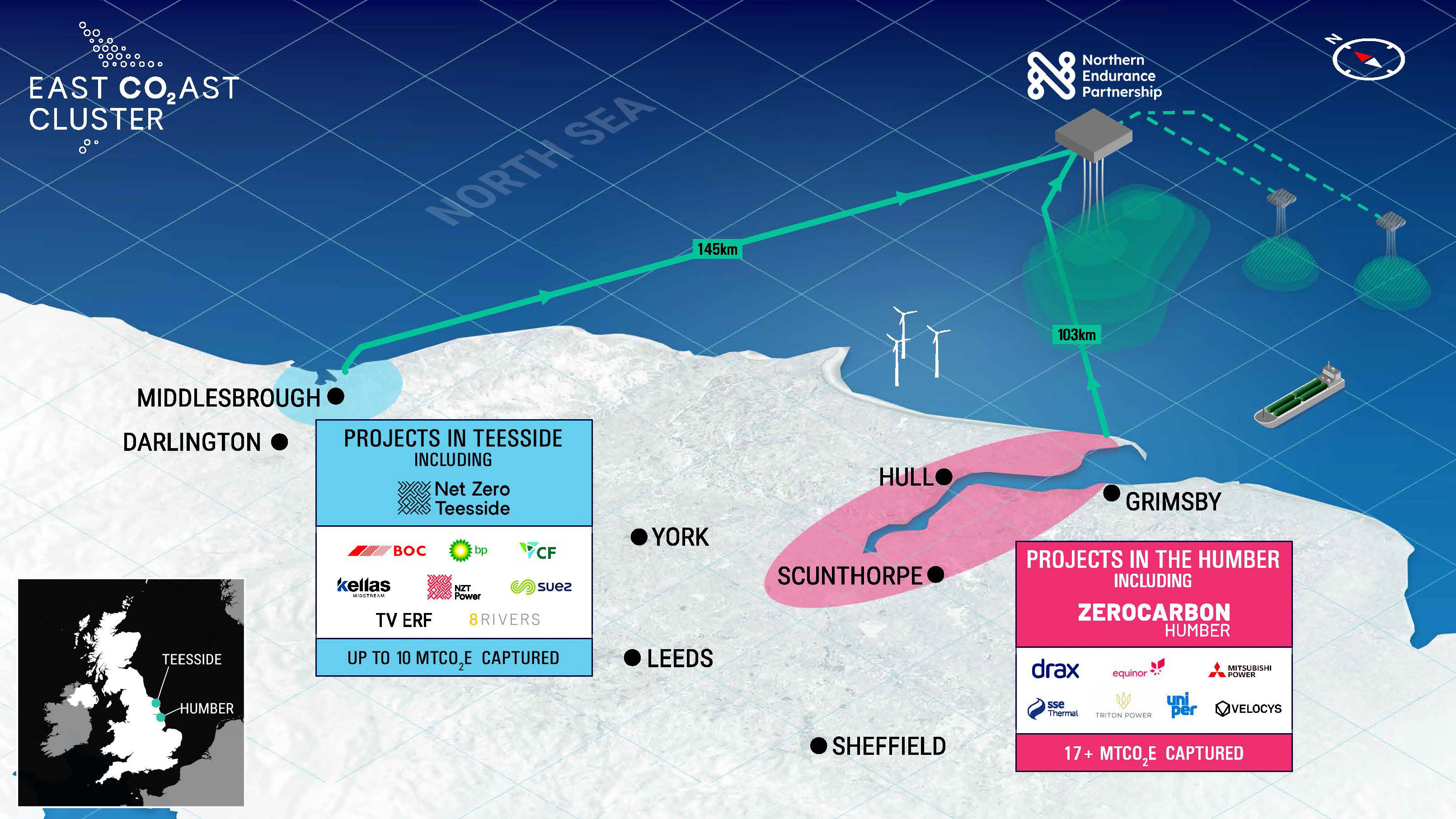

East Coast Cluster

One example in the UK, now being followed with interest in other parts of the world, is the East Coast Cluster (ECC), which is designed to remove 50% of the UK’s industrial cluster emissions some way in advance of the large-scale deployment of hydrogen or indeed other clean energy technologies. The ECC is a good example of joined up thinking, working with what we have and with the remaining concentrations of heavy industry to take carbon out of the atmosphere.

‘We think we can get to about a billion tonnes of stored carbon,’ said ECC Managing Director Andy Lane, who also leads the Northern Endurance Partnership and is BP’s Vice President for CCUS solutions. He described the ECC as the UK’s ‘enabling journey to net zero…’, notably for heavy industry sectors such as iron and steel, chemicals and cement.

This of course is meat and drink to someone like Aker’s David Phillips, who agreed that the UK and other countries are only just starting to come to terms with the need to scale up CCUS quickly while at the same time plugging it in to the industrial infrastructure. ‘The market [for CCUS] is only just starting to get moving and we need to prove up storage to capture enough carbon dioxide,’ said Phillips. ‘The big mismatch for us has been scale – how much carbon we can store and how much we can use.’

The use side of this equation covers everything from chemicals to concrete and using CO2 as a basic feedstock for a whole range of other industrial materials. If this works – and there is plenty of clean tech evidence to suggest it will – this will both help to drive transition and take the pressure off storage.

In the case of the ECC, this means building two pipelines in the Humber region to transport captured low carbon hydrogen and CO2 from major emitters such as Drax and British Steel, making industrial use of some of the captured material and sending the rest offshore for storage. ‘We are building the infrastructure for transporting and storing carbon,’ said Lane.

As far as the energy mix and transition go this seems like a reasonable interim solution. We need hydrogen at scale, but it is not here yet and aside from those long-winded and expensive nuclear options there are no other obvious industrial options on the horizon at the moment. Yes, you can electrify the fleet and stick heat pumps and solar into any building that can take them, but you still need some kind of combustible – dare I say explosive – power for heavy industry.

East Coast Cluster overview

Source: East Coast Cluster

North-west Hynet

On that tack, amongst others, there is Hynet, the UK’s second priority cluster for the north-west region. By extracting hydrogen as part of the CCUS process, Hynet offers a ‘win win’: aiming to reduce CO2 emissions by 10mn t/y by 2030 and helping to build the UK’s hydrogen economy. ‘We are initially building two blue hydrogen production plants and will be looking to deliver 4 GW of low carbon hydrogen by 2024,’ said Hynet Project Manager Rachel Perry.

By using CCUS to extract, transport, use and store CO2 from industry in the region we have what could be described as an energy ‘virtuous circle’ – fossil energy to blue hydrogen, which is then added to the UK’s industrial energy mix. ‘This is a new way of thinking,’ said Perry. ‘You have to be fast, nimble and innovative. We’re doing a huge amount of stakeholder engagement, for both the CO2 pipeline and for our hydrogen network.’ Industry, transport and homes should all end up with hydrogen energy as a result of Hynet.

A key challenge, it seems, is getting the connected, joined up thinking for sharing costs and producing a fully integrated solution. In the case of Eni UK, there is the end-of-life payback of repurposing existing oil and gas assets for carbon storage. According to Eni’s Martin Currie, who is Director of Liverpool Bay CCS, end-of-life wells in the region were suitable for storing up to 10mn tonnes of CO2 and had very low compression costs.

‘The complexity,’ he admitted, ‘is our interaction with other partners but this should help to protect existing jobs and create new ones in the region. Companies are already setting up because they know there is a CO2 transportation and storage project in the area.’

A key challenge, it seems, is getting the connected, joined up thinking for sharing costs and producing a fully integrated CCUS solution.

Strategic pathway

In fact, argued Currie, the UK is currently the best place to be for CCUS and the government has set out a strategic pathway which is starting to produce results. One of them, arguably, is the Whitetail Clean Energy project, a proposed zero emissions power plant to be built on the Teesside Wilton International site of energy services company Sembcorp.

The plant would generate zero emissions by burning natural gas with pure oxygen, said Sembcorp’s Corporate Affairs Director, Michael Jenner, making it more efficient and faster than a conventional plant relying on CCUS – and with half the carbon footprint. ‘Up to 98% of the carbon from this plant will be captured,’ he said.

The impetus for transition should be lots of innovation alongside practical deployment. ‘We need to be investing in kit,’ noted the National Grid’s Duncan Burt. ‘But there is also a need for more manufacturing partnerships. We have a target to operate the grid at zero carbon by 2025 and we want to see the UK and the US co-operate very hard to get to net zero by 2035. This will provide the engine room for green hydrogen, EVs and a whole range of digital integration technologies.’

Now louder than ever against the backdrop of conflict in Ukraine and geopolitical instability, is the call for greater energy security, certainly at national level but also locally too. Weaning Europe off Russian gas is part of the problem; the other side is speeding up the momentum of transition to ensure effective, secure and affordable alternative sources of energy. Nuclear and renewables, certainly, but also blue hydrogen as discussed and, where available, home produced, CCUS-abated fossil fuel for the foreseeable.

The downside of CCUS, as noted, has been cost and a failure to scale up, but the UK clusters should start to produce full chain capture. Even with shared costs and risks ‘these projects are still really expensive’, said Liz Blunsden of the law firm White & Case, ‘and they cost a lot more than the value they can produce in the market’.

The long-term value of CCUS, though, is the cost down the line of inaction today. Inevitably there was talk at International Energy Week of carbon markets and, post COP26, what ought to become the rising cost of carbon.

China, noted Qi Wang, Minister Counsellor at the Chinese Embassy in London, has created the world’s largest carbon market involving 2,000 companies and accounting for over 1bn kW of energy. What’s more, he said China is contributing to the UK’s own net zero target by supplying the country with electric buses and taxis. The Russian energy company Gazprom, which still earns as much as $200mn/d selling gas to Europe, should perhaps sit up and take note.